(

Taxonomy of Objections)

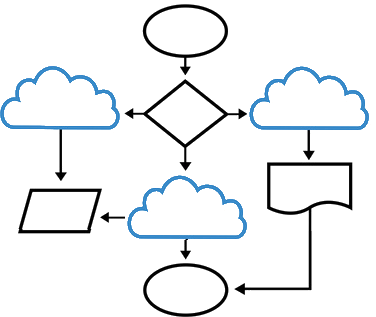

This post is the first substantive entry in my series about effective altruism. In a previous post, I offered a general introduction to the topic of effective altruism (EA) and sketched out a taxonomy of the main objections to the practice. In that post, I adopted a ‘thick’ definition of EA, which holds that one ought to do the most good one can do, assuming a welfarist and consequentialist approach to ethics, and favouring evidentially robust policy interventions. I identified nine major objections to this form of thick effective altruism, divided into three main families. The diagram above depicts all of this.

In today’s post, I want to take a more detailed look at the first family of objections: the justice family. The gist of the justice objection is that thick EA fails to appropriately weigh justice-relevant conditions when assessing the policies that ought to be favoured by its adherents. This objection takes three forms: (i) the equality version; (ii) the priority version; and (iii) the rights version. Let’s look at each objection and the possible responses from the proponents of EA.

As with all the entries in this series, what follows is based closely on Iason Gabriel’s excellent article ‘

What’s wrong with effective altruism?’. I will add some commentary of my own along the way, but I can’t claim any originality for the main points.

1. The Equality Objection

Gabriel notes that most EAs appreciate the instrumental value of equality (understood broadly here to include equality of outcome and opportunity). Inequality of outcomes can often be an impediment to securing other goods and can give rise to ‘resentment, domination and the erosion of public goods’ (Gabriel 2015, 4). Furthermore, the welfarist philosophy underlying EA is committed to the concept of marginal utility. This concept implies that more good can be done by giving something to the poor than by giving the same thing to the relatively wealthy. This is heavily emphasised in all the EA literature I have come across.

Nevertheless, despite this instrumental appreciation of equality, critics charge that adherents of EA do not appreciate the intrinsic good of equality. Gabriel makes the point using a thought experiment.

Two Villages: There are two villages in two different countries, both in need of assistance. There are two possible policy interventions which could be funded (the funding being the same for both). The first intervention would allocate money equally between the two villages, supporting the same projects in both and achieving a substantial overall benefit. The second intervention gives all the money to one of the villages. By doing so, the second intervention achieves a marginally greater overall gain in welfare. Which intervention should you favour?

To be consistent with their welfarist and consequentialist philosophy, the proponent of EA would have to favour the second intervention, even though it pays no heed to the intrinsic value of equality. This is a problem according to the critic.

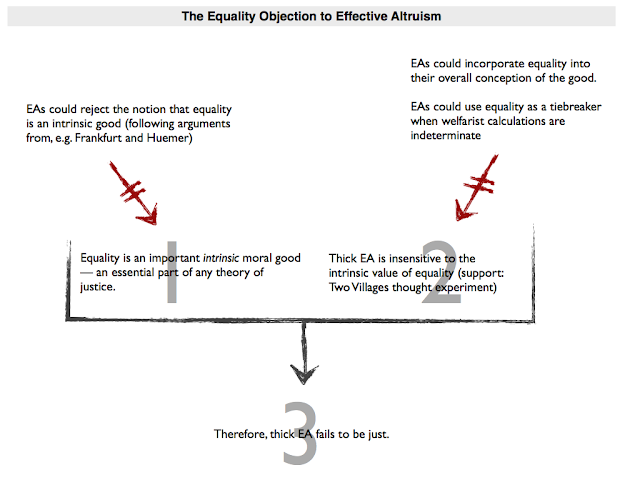

Let’s formalise this into an argument objecting to EA:

- (1) Equality is an important intrinsic moral good — an essential part of any theory of justice.

- (2) Thick EA is insensitive to the intrinsic value of equality (support: Two Villages thought experiment)

- (3) Therefore, thick EA fails to be just.

Is this a serious objection? Gabriel is non-committal in his analysis, but notes that there are several plausible lines of response available to the proponent of EA. The first is simply to reject the guiding normative premise, i.e. reject the notion that equality is an intrinsic moral good and an essential part of any theory of justice. This might seem unpalatable at first glance, but there are several philosophers who defend the notion that equality is not an intrinsic good. For example, Harry Frankfurt has recently penned

a short book defending this proposition, and libertarians like

Michael Huemer have offered sustained objections to it in the past. The advantage of this response is that EA is still perfectly well able to address the instrumental value of equality in its assessments. This, in turn, mitigates the initially negative reaction to dropping the intrinsic value of equality.

Maybe that’s a step too far for some people. If so, there are other ways to reconcile EA and equality. One is to broaden one’s conception of the good so that equity becomes part of the welfarist system of values. Welfarism, as it is typically conceived, focuses on a narrow set of well-being metrics, including things like absence of pain, lifespan, improved educational attainment and so forth (more on these metrics in a future entry in this series). This set of metrics could potentially be expanded to include equality of outcomes. Gabriel channels Samuel Scheffler on this point, noting that one could adopt a ‘distribution-sensitive conception of the overall good’. The problem with this is figuring out the weight that should be attached to equitable distributions in the assessment of outcomes.

Another possibility would be to allow equality to be used as a tie-breaker when other welfare-based comparisons are indeterminate. This would accommodate some of the intuition behind the equality objection, albeit not all of it.

In sum, it’s not clear how serious the equality objection is to the EA project.

2. The Priority Objection

The second variant on the justice objection focuses on the concept of priority. This features in many accounts of distributive justice. A pure form of distributive egalitarianism would treat everybody equally. So if there was $1,000,000 to be divided up between a population of 1,000, everybody would get an equal share of $1,000. This pure egalitarianism does not sit well with many people. The problem is that in a population of 1,000 there are likely to be important differences when it comes to how much some people deserve to receive. For example, some people might be independently wealthy and so not in need of $1,000. Some people might have been wealthy before, but gambled away all their money on speculative investments. Such people would be less deserving of the money than someone who was deprived through no fault of their own. The concept of priority is introduced so as to pay heed to these differences in deservingness.

What this means in practice is that distributions should usually favour the worst off. In other words, they should get priority when it comes to divvying up things like social spending or charitable giving. Ostensibly, thick EA pays heed to this prioritarian vision of justice. If you read books like MacAskill’s

Doing Good Better, the message clearly seems to be that we should donate to the ultra poor. The critic argues that thick EAs are not true prioritarians in practice. They favour interventions that are cost-effective and result in the greatest marginal gains in welfare. The problem is that interventions favouring the poorest of the poor are unlikely to be both cost-effective and result in the greatest marginal gains in welfare. The poorest of the poor suffer from complex, multidimensional forms of deprivation that are difficult to overcome via any one policy intervention.

Once again Gabriel makes the point using a thought experiment:

Ultrapoverty: In a developing country, many people are living in extreme poverty. Some of those people are worse off than others. As an EA you have to choose between two possible policy interventions. The first focuses on those who can benefit the most: urban literate men. The policy is very successful in lifting them out of poverty. The second program focuses on those who are worst off: illiterate widows and disabled persons living in rural areas. It has some success, but less than the first program.

The claim is that the thick EA would have to favour the first policy in order to be consistent with their welfarist and consequentialist philosophy. This means they are not truly sensitive to the prioritarian vision of justice.

To formalise this, we can say:

- (4) Any complete vision of justice ought to include a prioritarian condition when it comes to distributions of benefits and burdens, i.e. it ought to favour those most in need.

- (5) Thick EAs are insensitive to the prioritarian condition (support: Ultrapoverty thought experiment)

- (6) Therefore, thick EA fails to be just.

What can be said in response? Gabriel suggests four possible replies.

The first is to bite the bullet and reject the prioritarian condition. Again, this might seem like an unpalatable thing to do. The prioritarian view has a certain intuitive appeal. But there are philosophers who reject it. For instance, Huemer,

in the paper linked to previously, critiques the prioritarian view. But this critique has limited scope, applying only when certain other conditions are met. Furthermore, even with this limited scope, Huemer’s view is not beyond criticism and has, indeed, been

recently challenged by Pierre Cloarec. Still, it’s not beyond the realm of possibility to reject prioritarianism.

A second response is to incorporate the prioritarian condition into their welfarist calculus, possibly on a defeasible basis. Gabriel notes that some large charitable foundations, such as the Gates Foundation, already incorporate priority rankings into their decision-making. This suggests that this particular criticism of EA may be more theoretical than practical. A third response would be to use priority as a tie-breaker in cases where the welfarist calculation is indeterminate or equivalent between two policy interventions.

The final response is slightly more theoretical. One justification of the prioritarian view holds that it is important because it legitimises the state’s actions. That is to say, in order for the state to legitimately hold coercive power over its citizens, its institutions must be justified to the worst-off in society. This is one of the ideas in Rawls’s

A Theory of Justice. Given this theoretical grounding, a proponent of EA may be able to step around the prioritarian critique by arguing that they are focusing on private donations. The claim would be that private donations are not subject to the same need for legitimation and hence the priority condition can be ignored. The problem with this is that it feels like the EA gets off on a technicality, and I’m not sure how defensible it is in a world in which private interests hold considerable state-like power (this being one of the critiques of large philanthropic donations like those emanating from Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg).

3. The Rights Objection

The final justice-related objection focuses on rights. Most people know what rights are. They are those somewhat elusive moral-legal entities that entitle you to make claims on others and impose duties upon them. They could include things like the right to bodily integrity, freedom of conscience, property, education and so on. Following Dworkin’s classic metaphor, rights are sometimes said to operate as ‘trumps’ in political and legal decision-making. You cannot sacrifice someone’s rights to the greater good.

The critic of EA worries that it is not sensitive to the trump-like quality of rights. EA’s may be able to respect rights in a defeasible manner, perhaps by accepting that respecting rights is a decent heuristic to follow when trying to secure the optimum marginal welfare gains. But such defeasible support for rights is insufficient for the critic. Another thought experiment can be used to make the point:

Sweatshop: You are working in a developing country that has seen a remarkable growth in dangerous and poorly regulated factory labour (‘sweatshop labour’). This has lifted many people out of poverty, but led to an increase in workplace fatalities. Some NGOs want to campaign for better working conditions (‘workers’ rights’). They ask you for money. You have reason to believe that your donation would enable them to persuade the government to introduce a workers’ rights charter. But the effect of this would be to reduce the number of employment opportunities in the country, thereby preventing many people from escaping poverty. What do you do?

This thought experiment is a little less hypothetical than the preceding ones. If you read MacAskill’s

Doing Good Better you will find a robust defence of sweatshop labour on the grounds that it is undoubtedly good for the poor. But the rights theorist may balk at this. They would argue that favouring sweatshop labour involves an impermissible tradeoff between the rights of the workers and the greater good.

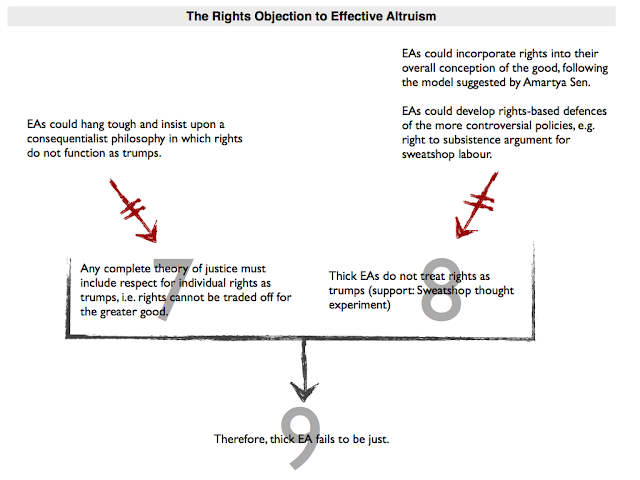

To put this formally:

- (7) Any complete theory of justice must include respect for individual rights as trumps, i.e. rights cannot be traded off for the greater good.

- (8) Thick EAs do not treat rights as trumps (support: Sweatshop thought experiment)

- (9) Therefore, thick EA fails to be just.

This objection mimics the standard deontological objection to consequentialist ethical theories. According to the critic, rights operate as deontological side constraints to decision-making. Can the proponent of EA address this problem? Gabriel identifies three responses.

The first is to try to incorporate rights into the overall conception of the good that motivates the EA position. This is not as unusual as it might first sound. Amartya Sen has argued (LINK) that respect for rights should be included as an additional factor in the overall assessment of the good. They would be included alongside the welfare assessments that are common to EA; they would not be reducible to such welfare assessments. In other words, when assessing the merits of some policy intervention, EAs should try to include respect for rights and gains in welfare in their assessments. This might lead them to conclude that the welfare gains from sweatshop labour are offset by the rights violations.

The second response is to hang tough and insist upon the consequentialist analysis. In other words, to insist that in at least some cases gains in welfare trump rights. I tend to find this appealing for reasons discussed elsewhere on this blog. I am broadly in favour of consequentialist approaches to ethics and find many standard deontological objections unpersuasive. For instance, the most common objection to consequentialism is that if you follow its advice to the hilt you will end up doing some seemingly bad things. But

as Pettit points out, in most such cases, following the deontologist’s advice also requires some bad things. This is because most such objections to consequentialism involve dilemmatic decision problems in which no course of action is 100% desirable. Thus, in these cases it still seems like assessing the overall outcomes is the best way to go. That’s not to say it’s easy to assess those outcomes and to figure out what should and should not go into our assessment of the good; but it is to say that insisting on deontological constraints is not as compelling as some seem to believe.

The third response would be to develop rights-based defences of things like sweatshop labour to back up the initial welfarist assessment. Gabriel briefly alludes to this possibility. He suggests that the sweatshop labour example involves a tradeoff between a right to subsistence and a right to reasonable working conditions. In this case, the right to subsistence might win out. However, Gabriel reneges on this position because he accepts an argument made by Henry Shue which claims that subsistence includes security in the possession of what one needs to get by. The concern then is that sweatshop labour wouldn’t include that security.

4. Conclusion

To briefly recap, the three justice objections all claim that EA is deficient because it fails to incorporate some justice-relevant condition. As outlined above, there are various ways that the proponent of EA can respond. These typically reduce to either hanging tough with their welfarist-consequentialist approach to assessing policies; or modifying their view to incorporate the relevant conditions.

Although I have covered these objections in quite some detail, I have to say that I find these to be the least interesting objections to EA. It’s not that the points raised are unimportant. It’s just that they are all really about the moral theory underlying the EA position. It’s always possible for the proponent of EA to amend their moral theory so as to align more closely with our moral intuitions. The real issue is whether those amendments undermine other aspects of EA, such as its insistence on useful objective metrics for assessing policy interventions. That’s what the next set of objections will deal with. Stay tuned.